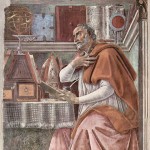

St. Augustine: The Once and Future Giant

August 28th. is the feast day of Aurelius Augustinus Bishop of Hippo.

St. Augustine (354 to 430) was one of my boyhood heroes. I read Louis de Wohl’s biography of the saint, The Restless Flame. As a German writer in the 1920’s and 1930’s, de Wohl was immensely successful as a writer of thrillers and he brought this sense of action to his religious historical novels written in English after World War II. I was introduced to Augustine as a man of great learning and action, a man who moved mountains and changed the course of oceans of thought and action.

Later, when I read his Confessions and the City of God in Latin, I met a more complex man, very much at odds with mid-twentieth century psychology. Yes, Augustine was a giant of Western thought, but he was also a major force for movements and institutions that had been blown apart with the end of the modern era when World War II left Christendom in smoke and ashes.

The alliance of empire and church, the oneness of truth that allowed for state violence to save those in rebellious error, the primacy of celibacy, and the utterly fallen nature of humans conceived in original sin are significant positions which post-modern thinkers judge to have been more harmful than helpful.

The development of history as a critical discipline in the 19th century blossomed in the 20th with the tools of science, linguistics, and anthropology. The political, human, and moral catastrophes of saturation bombing, genocide, and nuclear weapons have led to a profound soul searching about what brought us to this point. Needless to say, many of Augustine’s positions came under fire by revisionists.

John J. O’Donnell, in Augustine: A New Biography, presents Augustine as a man of his time, with more warts and wrinkles than a halo. The dreaded heresies Augustine defeated, Donatism and Pelagianism, come in for a revisionist appraisal of their good points. David Hunter, in his review of O’Donnell’s book in America magazine, takes the author to task.

“This Augustine will surprise many readers. The following section headings, although taken from a single chapter, characterize the tone that prevails throughout the whole book: “Augustine the Self-Promoter,” “Augustine the Social Climber,” “Augustine the Troublemaker.” O’Donnell’s Augustine never seems to have outgrown his youthful aggressions and ambitions: “When writing about his first book in the Confessions, he reproached himself for his worldly ambition, even as, with the Confessions, he was carrying out an ecclesiastical version of the same social climbing.” O’Donnell duly documents Augustine’s later associations with powerful Roman generals as evidence of his subject’s lifelong attraction to power.”

O’Donnell has tremendous crediblity as the author of a three volume commentary on the Confessions of St. Augustine. However, his critics excoriate his portrayal of Augustine as less than saintly.

St. Augustine will rise again after this bout of historical criticism because the positive aspects of his legacy, his passionate devotion to Christ, his attempts to build a theology on scripture, the constitution of the human being as being body and soul, and the power of love, will, and memory will all come to the fore once again. From time to time St. Augustine may suffer from our ambivalence, but he is the pivotal ancestor that believers and non-believers in the post-modern world cannot deny.

Take a look at O’Donnell’s profile on the Georgetown University website and select some of the reviews. It’s an eye opener.

Read More